History of Fort Tabby by Kerry Ross Boren

How Tabiona Got It’s Name, by Kerry Ross Boren.

Tabiona is a town in Duchesne County, Utah. Southeast of Tabby Mountain on the Duchesne River. The elevation is 6,516 feet. The population was 171 on the 2010 United States Census. Because of its small population, Tabiona has always housed all 12 grades in the same building, though grade school students attend classes in a separate wing of the building. Tabiona High competes as a 1A school in athletics and the school mascot is the Tiger. The school colors are purple and white. Tabiona has a rich tradition in basketball.

When the white settlers first arrived in Utah, Tabby was a young man, but already a leader of one of the many bands of Utes in central and eastern Utah. Despite early conflict in Utah Valley and more serious outbreaks in the 1850’s led by Chiefs Wakara (Walker, Walkara) and Tintic, the settlers and the Native American under Chiefs’ Sowiette and Tabby lived in relative peace.

After the Mormon pioneer established Fort Utah along the Provo River in the northern part of Utah Valley, there began to be significant conflict between the pioneers and the tribe that lived along the Provo River. In February 1850, Brigham Young issued an extermination order of the Timpanogos in all of Utah Valley. When the Mormon militia attacked the Timpanogos along the Provo River, the main party fled to southern Utah Valley, where Chief Tabby’s band was situated. The Mormon militia then came to the Timpanogos villages along the Spanish Fork River and the Peteetneet Creek. The Mormons promised to be friendly to the Timpanogos, but then lined up the men to be executed in front of their families. Some attempted to flee across the frozen lake, but the Mormons ran after them on horseback and shot them. At least eleven Timpanogos were killed. Altogether, 102 Timpanogos were killed in the Battle at Fort Utah. The Timpanogos who had died were decapitated and left unburied. When Chief Tabby returned with Chief Peteetneet and Grospene, they found the decapitated bodies of their band members and angrily confronted the settlers at Fort Utah

In 1860 a military fort was built near the current town location. The fort was named Tabbyville, and Fort Tabby until 1915. In 1865, a treaty was signed requiring the Indians to move to the Uintah Reservation, which had been established by Abraham Lincoln in 1861. Lieutenant Pardon Dodds, the first official Indian Agent, built a log cabin and a fort in 1864 on the upper Duchesne River, one mile above Tabiona, which was used by soldiers during Indian uprisings. The Agency was moved to Ft. Duchesne in 1868. Later the cabins (located in Tabiona) was burned and rocks from the chimney, which stood as a landmark for many years, were used to build a monument (by the D.U.P).

Tabiona was so named in honor of Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah, who frequently made his camp there on his trips between Heber City and the Uintah Basin. Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah (or Tabby, Tabiona, or Tabiona, 1789-1898) was the leader of the Timpanogos when they were displaced to the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. He rose to power as a young man and was a sub-chief under his cousin Chief Walkara when the Mormon pioneers first arrived in Timpanogos territory. He was one of the principal clan leaders over a band in southern Utah Valley, along with Chief Peteetneeet and Grospene. He was a grandson of Turunianchi, who was the leader when the Timpanogos first contacted the Europeans during the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition. Turunianchi’s grandsons made up the royal line of “brothers” (even though some were cousins) referred to by Brigham Young.

Chief Tabby was instrumental in trying to establish peace between the Mormon pioneers and the Timpanogos. He was one of the main chiefs that sat in peace negotiations and signed the Shoshone Goship treaty of peace in 1863, and the Spanish Fork Treaty in 1865. When Antonga Black Hawk led the Black Hawk War in Utah, he led the Timpanogos who wanted peace on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. While he strove to have his people follow the terms of the Spanish Fork Treaty, the US government did not follow their side of the treaty, partially because Brigham Young did not have authority to speak for the US government. As a sign of protest, he led the Timpanogos unto Thistle Valley in Sanpete County to hunt and dance in the spring of 1872. This made the American uneasy, and he was able to get the American to fulfill their obligations for that year.

Tabby-To-Kwanah, whose name means Child of the Sun, and his people interacted peaceably with the whites for several years. However, by the early 1860’s white-Indian conflicts intensified and the federal government decided that the Native Americans should be placed on reservations for mutual safety and so the settlers could occupy more land. The treaty of 1865 relegated the Uintah Utes to the Uintah Basin. If the Indians would move there, they would receive payment for their land- including the Indian farms at Spanish Fork and Sanpete they were giving up- and services and supplies from the government. Sixteen chiefs signed the treaty, but Congress did not ratify it. The treaty goods and money were never delivered, and the Indians continued to roam in search of food. For Chief Tabby and his people, who traditionally located seasonally in the Uintah Mountains and Uintah Basin, the transition was not as difficult as for some bands, but all were distressed when the government did not deliver their “presents” and they faced constant hunger. Many Indians, angry about being forced off their native lands, rebelled under Chief Black Hawk. The more peaceful one went with Tabby to the reservation and avoided bloodshed, although greatly disappointed in the word of the white man.

During 1865-68 followers of Black Hawk terrorized the settlers, stealing livestock and occasionally killing isolated whites. Because there had been little problem with Tabby’s Utes, on of the first acts of the Wasatch Militia was to make peace. According to Joseph S. McDonald, a member of the militia, Captain Wall and 24 men from Heber City took three wagon loads of supplies, plus 100 head of cattle as a gift from Brigham Young, to the reservation as a peace offering. The goods were taken to the Indian Agency on the west fork of the Duchesne River, where the Indians were gathered. Many males had gone to fight with Black Hawk, but tensions remained high. Even Tabby was angry, feeling betrayed by the white man, and he warned of possible trouble. The militia prepared defenses at the agency and waited three days for an attack. About 275 warriors surrounded the area. Tabby was inside the agent’s cabin when Captain Wall decided that it was time to talk. For three hours Tabby and Wall negotiated and then met again the next day. At last Tabby agreed to peace and accepted the cattle and supplies. The warriors, still hot for battle, were quieted by Tabby. Some young men were difficult to restrain, though, and incidents of raiding livestock continued. Heber City remained on guard, but for the most part Tabby’s followers avoided warfare.

In August 1867, according to John Crook, Chief Tabby and his whole band came to Heber for a peace feast. Large tables were set up in the bowery, and towns women made a “good picnic” for Tabby and his people. An ox was roasted barbecue style, ad everyone filled up on food. The Indians stayed a few days and then went home with presents of food. This picnic created good will, and there were few raids in Wasatch County afterwards.

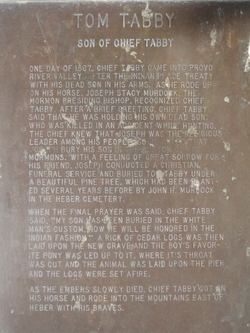

It was during the Black Hawk War of the mid-1860s that Tom Tabby died accidentally while hunting. Chief Tabby, whose people had once freely roamed the Provo River Valley, in which Heber City is located, carried his dead son in his arms to the town hoping that the boy could be buried there. Joseph Stacy Murdock consented to conduct a Christian burial service. According to a plaque at the cemetery, following the funeral Tabby said, “My son has been buried in the white man’s custom, now he will be honored in the Indian fashion.” The Indians laid cedar logs on the grave, led the boy’s favorite pony to the logs where it was killed, then ignited the funeral pyre. When the blaze had died to embers, the saddened chief mounted his horse and with his companions rode east, to the reservation. Chief Tabby, the seeker of peace between the Native American and the settlers, had demonstrated his commitment to seek the best of both worlds rather than fight.

By 1868 the Black Hawk War was basically over, and by 1869 most Utes were located on reservation lands. Tabby’s good judgment, pragmatism, and ability to compromise won hi respect from both sides. However, Tabby was not one to sit idly by and watch his people starve when the agents failed to provide necessities. In the spring of 1872 (at 83 years old), when provisions were inadequate and his people were hungry and frustrated, Tabby, as a sign of protest, led them off the reservation into Thistle Valley in Sanpete County on a hunting trip and to hold their ritual dances. The large group of Utes made the settlers uneasy, but the move got the attention Tabby wanted to make his grievances known. Dan Jones and Dimick Huntington, who were sympathetic with the Utes, convinced Agent Critchlow, Colonel Morrow from Camp Douglas, and local community leaders to meet with the Indians. Tabby explained his people’s dissatisfaction with conditions and lack of supplies on the reservation. He said they would “as soon die fighting as starve.” Federal officials assured the Utes that supplies would be sent, and the Utes returned to the reservation. Luckily, for once the promised supplies did arrive. For many years, Tabby continued as an effective leader, serving his people, working for their rights, and maintaining peace.

The small settlement, wich was first and Indian cam and then a for in 1860, and an Indian Agency in 1864-1865, was first called Tabbyville and Tabby, and was further bolstered by and influx of settlers following the opening of the reservation to white settlement in 1905. By 1915, the old titles were abandoned in favor of Tabiona, in honor of the old Chief, who died in 1898 at the age of 109, but who claimed to be much older.

Tom Tabby Headstone

In the quiet solemnity of the Heber City cemetery stands a simple sandstone marker bearing the initials T. T. A huge pine tree towers over the grave, shadowing the burial place of Tom Tabby (also known as Tabby Tom), son of Tabby-To-Kwanah. Chief Tabby wanted his son buried in the way of the Mormons; therefore, Tom Tabby’s remains were laid to rest among the graves of the Murdock family rather than on the reservation land.